Longboats

The longboat was just that. It was the largest and most heavily built boat carried by a ship. Longboats were generally scaled to the ship they served, with one-third to one half the length of the ship’s keel providing the size for the boat. It was sometimes towed behind, but at sea was almost always carried safely on deck. One has to marvel at the skill of the sailors in hoisting aboard such a large and unwieldy object.

Link to the Mayflower replica in the USA.

The longboat was a general utility boat. It was used for carrying people and provisions to and from shore; it might be sent with the watering party and their water casks; and in times of war might carry a cutting out party, with oars muffled, in among anchored enemy shipping. In calm conditions it could be used to tow the ship into harbour or away from a dangerous reef; and one can imagine the sweating and exhausted sailors putting the backs to the oars as they attempt to extricate the mother ship from the clutches of the rocks.

As the main utility boat it had to be able to operate in any weather under sail or oars. The reason for the long boat’s size has to do with her original purpose which was to “carry forth and weigh the sheet anchor”. This was often necessary in the days of sailing ships in order to manoeuvre in harbours and river mouths where it was too tight to work under sail. A second anchor would be rowed out to the full length of the anchor rope (known as the rode by sailors), and then the ship hauled up to the new position. The Batavia’s main anchor would have weighed about 3 tonnes and it would be lashed under the longboat in order to “carry it forth”.

The VOC longboats were flat bottomed and carried two lee boards to provide the lateral resistance needed for sailing. They make for interesting sailing as they, along with the sails, need to be manhandled on each tack.

The Leeboards

Leeboards are typical of Dutch and English vessels operating in the swallow tidal waters of the South East of England and the shifting sand flats of Holland. Boats were built flat bottomed in order to dry out safely at low tide, but in order to sail to windward they needed some form of lateral resistance. Leeboards were simple and strong and did not require a trunk to be built for a centreboard.

Have a look at some other beautiful leeboards at www.leeboards.com

Replica Ships

Western Australia has been lucky enough to see a number of replica ships being built. The Endeavour and Duyfken were both built in Fremantle and were very historically accurate. The Endeavour now lives at the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney, while the Duyfken berthed again in Fremantle after a long stay on the East Coast.

The Batavia Longboat and the Duyfken sailing off Geraldton in 2004. Photo: Frank Sindelar

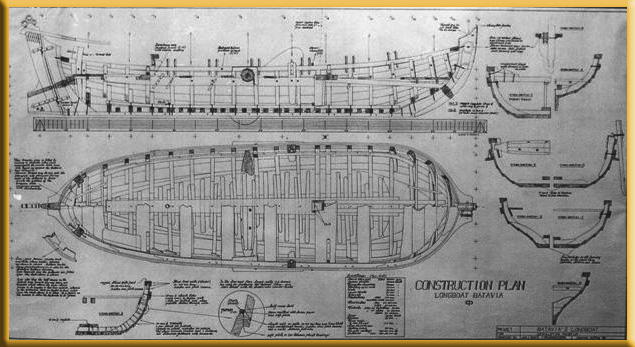

The Drawings

It was the vision of the Western Australian Museum Geraldton and the Central West College of TAFE to build a replica that could one day re-enact Pelsaert’s epic voyage. Building proceeded under the guidance of Les Crawley who instructed four apprentices; Felix Dubendorfer, Geoff Sherlock, Kim Hatfield and newcommer Erin.

The design for the Batavia Coast Replica was drawn by Adriaan De Jong, a naval architect with a great interest in historic craft. In his letter to the then curator of the Western Australian Museum Geraldton he wrote:

“In closing I should mention that the design is based on boat centres and a drawing in the books of Witsen and Van Yk, and the boat that was found with the (mostly Dutch built) ship Vasa. It appears that ships’ boats are fairly standard items for the whole of the 17th century and I am confident that this reconstruction will be quite close to the original boat of the ship Batavia.”

The plans that De Jong produced were for a flat bottomed open boat some 10.2 metres long and 3.0 metres wide. Its topsides were built up from overlapping planks in what is known as clinker construction, where each plank is fastened to the one below it by closely spaced copper rivets. This technique had already had a long history in European boatbuilding and could produce relatively light hulls that were resilient and flexible. The longboats were built with very full and buoyant bows in order to carry the massive weight of the ship’s anchor, while the sterns were much narrower and finer allowing the boat to be propelled more easily with oars.

Construction

Construction of the Longboat began with its flat bottom which was glued up from 40mm thick planks of celery top pine. Onto this base were fastened the frames and futtocks; the heavy sawn timbers that are fastened together to form the “ribs” of the boat. At this stage the stem and stern posts were also braced into position.

In the original boat each of these timbers would have been cut from a single large piece that already had a natural curve, but in this reconstruction they were laminated and glued. This is because of a lack of suitable timber; the 17th century shipwright would have had access to a ready supply of timber cut from different parts of the tree. Bends and elbows, branches, and even forks could find their way into the finished boat, and the boat builders were adept at selecting pieces to take best advantage of the natural grain strength. The modern boat builder has available perfectly sized straight grained boards, but is forced to laminate most things that require a curve. Fortunately the there was a small supply of oak left over from the Duifken project and many of these natural crooks were built into the Longboat as breast hooks and reinforcing knees.

In the original boat each of these timbers would have been cut from a single large piece that already had a natural curve, but in this reconstruction they were laminated and glued. This is because of a lack of suitable timber; the 17th century shipwright would have had access to a ready supply of timber cut from different parts of the tree. Bends and elbows, branches, and even forks could find their way into the finished boat, and the boat builders were adept at selecting pieces to take best advantage of the natural grain strength. The modern boat builder has available perfectly sized straight grained boards, but is forced to laminate most things that require a curve. Fortunately the there was a small supply of oak left over from the Duifken project and many of these natural crooks were built into the Longboat as breast hooks and reinforcing knees.

The next step was to install the keelson, an eight metre long plank that was cut from a single log of Kapur – an Indonesian hardwood. This log had been found floating in the harbour some years before and was donated by the Geraldton Port Authority to the Longboat Project. Cut with a portable chainsaw mill, this massive log provided the timber for the keelson, thwarts, frames and futtocks, leeboards, keel, and rudder. The keelson, firmly fastened though the frames and hull bottom, forms a kind of “I” beam that provides the main longitudinal strength for the Longboat.

With the keelson in place work could begin on the hull planking. This was a painstaking task that was to occupy the builders for many months. The timber chosen was Celery Top Pine that was specially imported from Tasmania. Planks for the bow and stern had to be bent into hard curves and to do this the timber needed to be steamed to make it pliable. Planks would be placed in a steam box for about twenty minutes before a team wearing thick gloves would pull it out and quickly try to clamp it in place. Speed is of the essence as the rapidly cooling timber quickly looses its flexibility. The planks would be left overnight to fix their new shape then removed and shaped as necessary before a scarph was cut in order to join it the next part. The planks were not long enough to run the whole length of the hull and usually two scarphs were required. After all this preparation the plank would be placed back in position on the hull and holes drilled to fasten it to the previous plank with copper rivets.

Geoff described the frustration when, after all that work, the plank can explode because of the built up tensions in the timber. Just the act of drilling a small rivet hole would sometimes cause the plank splinter and crack and then the whole job would have to begin again.